Why Understanding Historic Preservation Matters

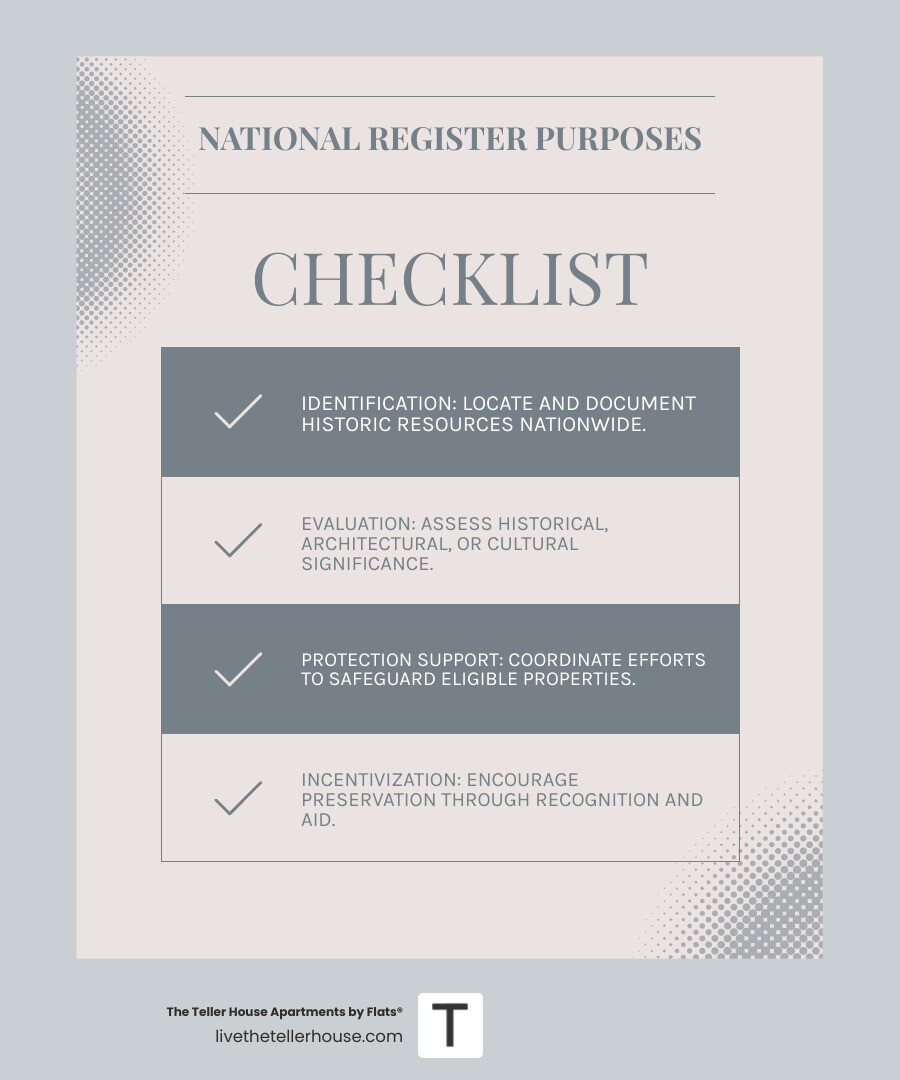

The national historic register serves as America's official list of buildings, districts, sites, structures, and objects worthy of preservation for their significance in American history, architecture, archaeology, and culture. Established by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, this federal program coordinates public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect our nation's historic resources.

Key Facts About the National Historic Register:

- Official Name: National Register of Historic Places (NRHP)

- Administrator: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

- Total Properties: Over 95,000 individual listings nationwide

- Contributing Resources: More than 1.8 million buildings, sites, structures, and objects

- Primary Purpose: Encourage historic preservation through recognition and incentives

Whether you're considering living in a historic building, curious about preservation tax credits, or simply want to understand how America protects its architectural heritage, the National Register affects communities across the country. From grand courthouses to modest neighborhood homes, these listed properties tell the story of our shared past while often serving vibrant modern purposes.

The program doesn't just create a list - it provides financial incentives for preservation, ensures federal projects consider historic resources, and helps communities celebrate their unique character. Yet many people misunderstand what listing actually means for property owners and residents.

What is the National Historic Register and Why Was It Created?

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is America's official inventory of buildings, sites, structures, and objects recognized for their role in the nation's story. Managed by the National Park Service, the program coordinates public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and support the preservation of significant places.

The story behind the national historic register begins in the post-World War II era, when rapid urban renewal led to the widespread demolition of historic buildings. A growing preservation movement resulted in the landmark National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. This act created the Register, established the Section 106 review process for federal projects, and created State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPOs) to assist with nominations and preservation matters.

The Mission Behind the Register

The national historic register's mission is to coordinate preservation efforts, identify significant places, and support public and private preservation through recognition and incentives. It serves as a planning tool, encouraging communities to consider historic assets. However, listing is not a guarantee of preservation. For private property owners using their own funds, the listing creates no restrictions. Protection is primarily enforced through the Section 106 review process, which requires federal agencies to consider the effects of their projects on historic properties.

Types of Properties Eligible for Listing

The national historic register accepts a diverse range of properties:

- Buildings: Structures designed to shelter human activity (e.g., homes, schools, churches).

- Structures: Constructions built for purposes other than shelter (e.g., bridges, lighthouses, grain elevators).

- Sites: Locations of significant events or archaeological findies (e.g., battlefields, prehistoric settlements).

- Objects: Smaller, often artistic or commemorative items (e.g., monuments, sculptures).

- Districts: Areas with a concentration of historic resources that form a cohesive whole. Properties within a district are classified as contributing (historically significant) or non-contributing (newer or altered).

The Path to Preservation: How a Property Gets Listed

Getting a property listed on the national historic register involves a multi-step process of research, state-level review, and federal approval. While anyone can start a nomination, it often involves collaboration between property owners and preservation experts.

Step 1: Research and Documentation

The nomination must prove a property's significance (its role in history, architecture, etc.) and its integrity (it retains authentic characteristics from its historic period). Integrity includes seven aspects: location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association. The research phase involves gathering historical documents and photos to build the case. The National Park Service offers guidance, such as NPS Bulletin 29: Researching a Historic Property.

Step 2: The State-Level Review

The completed nomination form goes to the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) for review. The SHPO provides public notification and presents the nomination to a state historic review commission. Private property rights are protected: an individual property cannot be listed if the owner objects, and a historic district cannot be listed if a majority of owners object.

Step 3: Federal Approval and Listing

After state approval, the nomination goes to the National Park Service for final review by the "Keeper of the National Register." The Keeper's office ensures the nomination meets all federal criteria, a process that typically takes 15 to 45 days. Once approved, the property is officially listed. The SHPO notifies the owner, who can then purchase a plaque from a private supplier.

Benefits, Incentives, and Common Misconceptions

Listing on the national historic register provides access to significant benefits but also comes with common misconceptions about property rights.

Financial Incentives for Preservation

A primary benefit is access to financial incentives, most notably the 20% federal investment tax credit. This applies to income-producing properties undergoing qualified rehabilitation that meets the Secretary of the Interior's Standards. The Historic Preservation Tax Incentives program has been crucial in revitalizing historic buildings nationwide. State-level credits and grants can often be combined with federal incentives. Additionally, property owners may receive tax deductions by donating preservation easements, which legally protect a building's historic character.

Beyond direct financial benefits, listing can also boost property values, attract heritage tourism, and foster community pride.

Understanding the Limitations of a National Historic Register Listing

A common misconception is that listing provides absolute protection. In reality, private property rights remain intact. A private owner using their own funds is not restricted by the listing and can alter or even demolish their property. The real "protection" comes through Section 106 review, which requires federal agencies to consider impacts on historic properties before funding, licensing, or permitting a project.

It's also important not to confuse national listing with local landmark designations. Local ordinances often have much stronger, legally binding restrictions on alterations and demolitions. While federal listing offers recognition and incentives, local designation provides regulatory control. Many properties benefit from having both.

Frequently Asked Questions about the National Register

What are the four main criteria for a property to be listed?

Getting a property listed on the national historic register isn't just about age - it needs to meet specific standards that prove its historical importance. Every property must satisfy at least one of four main criteria, plus maintain its integrity (meaning it still looks and feels authentic to its historic period).

Criterion A focuses on significant events that shaped our history. This could be anything from a building where important political meetings took place to a site connected to major social movements or economic developments. Many Chicago buildings qualify under this criterion due to their role in the city's industrial growth or cultural evolution.

Criterion B recognizes properties associated with important people from our past. This doesn't mean just famous presidents or generals - it includes architects, business leaders, social reformers, and others who made meaningful contributions to their communities or fields.

Criterion C is all about design and construction. This covers buildings that showcase distinctive architectural styles, represent the work of master builders or architects, or demonstrate important construction techniques. Historic bank buildings like ours often qualify here because they represent significant architectural achievements of their era.

Criterion D applies mainly to archaeological sites that can teach us about prehistoric or historic life. This criterion helps protect places where artifacts and other physical evidence can reveal important information about how people lived in the past.

Does listing on the Register restrict what a private owner can do with their property?

This is probably the biggest misconception about the national historic register - and the answer might surprise you. For private property owners using their own money, listing creates no restrictions whatsoever. You can renovate, alter, or even demolish a listed property if you're funding the work yourself.

The key word here is "federal involvement." Restrictions only kick in when you want to use federal money, apply for federal permits, or claim federal historic preservation tax credits. In those cases, any work must follow the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation - basically guidelines that ensure changes respect the building's historic character.

Think of it this way: the national historic register is more like a prestigious recognition program than a regulatory system. It opens doors to benefits and incentives, but it doesn't tie your hands as a property owner. This balance helps explain why so many private owners accept the listing process - they get the recognition and potential financial benefits without losing control over their property.

What is the "50-Year Rule"?

The famous "50-year rule" is actually more of a guideline than a hard-and-fast requirement. Generally speaking, properties need to be at least 50 years old before they're considered for the national historic register. This waiting period gives us enough historical perspective to judge a property's true significance.

But here's where it gets interesting - exceptional properties can break this rule. If a building has extraordinary national significance or outstanding architectural value that's already been recognized, it might qualify even if it's younger than 50 years. These exceptions are rare, but they do happen for truly remarkable places.

Historic districts work a bit differently. Even if some buildings in a proposed district are less than 50 years old, the district can still be listed as long as most properties meet the age requirement and contribute to the area's overall historic character. This flexibility helps preserve entire neighborhoods that tell complete stories about how communities developed over time.

The 50-year guideline makes sense when you think about it - it takes time to understand how a building or place fits into the bigger picture of American history and culture.

Conclusion

The national historic register represents far more than a government list—it's America's promise to future generations that we value the places that shaped our story. From grand courthouses to humble neighborhood homes, these 95,000 listings and millions of contributing resources create a living mix of our shared heritage.

What makes the Register truly powerful isn't just its recognition, but how it transforms preservation from a romantic ideal into practical reality. The 20% federal rehabilitation tax credit turns restoration dreams into viable business plans, while the Section 106 review process ensures that federal projects can't steamroll through history without careful consideration.

Yet perhaps the most beautiful aspect of historic preservation is how it bridges past and future. When a century-old bank building becomes luxury apartments, or when a forgotten warehouse transforms into vibrant community space, we're not just saving bricks and mortar—we're creating new chapters in ongoing stories.

At The Teller House Apartments, we witness this magic daily. Our residents don't just live in apartments; they become part of a continuing narrative that began when our building first opened its doors as a bank in historic Uptown Chicago. The original architectural details that grace our modern units remind us that good design transcends decades, while our contemporary amenities prove that historic buildings can accept the future without losing their soul.

This balance between preservation and progress defines the best of American historic preservation. By maintaining these significant places, we offer something increasingly rare in our world—a sense of permanence, character, and connection to something larger than ourselves.

Whether you're drawn to the stories embedded in old walls or simply appreciate the craftsmanship of bygone eras, historic buildings offer experiences that new construction simply cannot match. If you're curious about what it's like to call a piece of history home, we invite you to explore our Chicago Historic Apartments For Rent and find how thoughtful adaptive reuse creates truly unique living experiences.

Ready to become part of the story? Explore our historic Chicago apartments and see how we're contributing to the lasting legacy of our shared cultural heritage—one beautifully restored space at a time.